Fascist (insult)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Fascist has been used as a pejorative epithet against a wide range of people, political movements, governments, and institutions since the emergence of fascism in Europe in the 1920s. Political commentators on both the Left and the Right accused their opponents of being fascists, starting in the years before World War II. In 1928, the Communist International labeled their social democratic opponents as social fascists,[1] while the social democrats themselves as well as some parties on the political right accused the Communists of having become fascist under Joseph Stalin's leadership.[2] In light of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, The New York Times declared on 18 September 1939 that "Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism."[3] Later, in 1944, the anti-fascist and socialist writer George Orwell commented on Tribune that fascism had been rendered almost meaningless by its common use as an insult against various people, and argued that in England the word fascist had become a synonym for bully.[4]

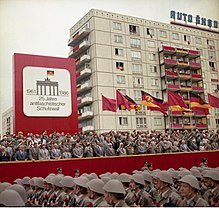

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union was categorized by its former World War II allies as totalitarian alongside fascist Nazi Germany to convert pre-World War II anti-fascism into post-war anti-communism, and debates around the comparison of Nazism and Stalinism intensified.[5] Both sides in the Cold War also used the epithets fascist and fascism against the other. In the Soviet Union, they were used to describe anti-Soviet activism, and East Germany officially referred to the Berlin Wall as the "Anti-Fascist Protection Wall." Across the Eastern Bloc, the term anti-fascist became synonymous with the Communist state–party line and denoted the struggle against dissenters and the broader Western world.[6][7] In the United States, early supporters of an aggressive foreign policy and domestic anti-communist measures in the 1940s and 1950s labeled the Soviet Union as fascist, and stated that it posed the same threat as the Axis Powers had posed during World War II.[8] Accusations that the enemy was fascist were used to justify opposition to negotiations and compromise, with the argument that the enemy would always act in a manner similar to Adolf Hitler or Nazi Germany in the 1930s.[8]

After the end of the Cold War, use of fascist as an insult continued across the political spectrum in many countries. Those labeled as fascist by their opponents in the 21st century have included the participants of the Euromaidan in Ukraine, the Ukrainian nationalists, the government of Croatia, former United States president Donald Trump, the current government of Russia ("Rashism") and supporters of Sebastián Piñera in Chile and Javier Milei in Argentina.

Eastern Europe

[edit]The Bolshevik movement and later the Soviet Union made frequent use of the fascist epithet coming from its conflict with the early German and Italian fascist movements. The label was widely used in press and political language to describe the ideological opponents of the Bolsheviks, such as the White movement. Later, from 1928 to the mid-1930s, it was even applied to social democracy, which was called social fascism and even regarded by communist parties as the most dangerous form of fascism for a time.[9] In Germany, the Communist Party of Germany, which had been largely controlled by the Soviet leadership since 1928, used the epithet fascism to describe both the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Nazi Party (NSDAP). In Soviet usage, the German Nazis were described as fascists until 1939, when the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was signed, after which Nazi–Soviet relations started to be presented positively in Soviet propaganda. Meanwhile, accusations that the leaders of the Soviet Union during the Stalin era acted as red fascists were commonly stated by both left-wing and right-wing critics.[8]

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, fascist was used in the USSR to describe virtually any anti-Soviet activity or opinion. In line with the Third Period, fascism was considered the "final phase of crisis of bourgeoisie", which "in fascism sought refuge" from "inherent contradictions of capitalism", and almost every Western capitalist country was fascist, with the Third Reich being just the "most reactionary" one.[10][11] The international investigation on Katyn massacre was described as "fascist libel"[12] and the Warsaw Uprising as "illegal and organised by fascists."[13] In Poland during the Polish People's Republic, communist propaganda referred to the Home Army (Polish: Armia Krajowa) as a fascist organization.[14] Polish Communist Security Service (Polish: Służba Bezpieczeństwa) described Trotskyism, Titoism, and imperialism as "variants of fascism."[15]

This use continued into the Cold War era and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The official Soviet version of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was described as "Fascist, Hitlerite, reactionary and counter-revolutionary hooligans financed by the imperialist West [which] took advantage of the unrest to stage a counter-revolution."[16] Some rank-and-file Soviet soldiers reportedly believed they were being sent to East Berlin to fight German fascists.[17] The Soviet-backed German Democratic Republic's official name for the Berlin Wall was the Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart (German: Antifaschistischer Schutzwall).[18] After the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai denounced the Soviet Union for "fascist politics, great power chauvinism, national egoism and social imperialism", comparing the invasion to the Vietnam War and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia.[19] During the Barricades in January 1991, which followed the May 1990 "On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia" independence declaration of the Republic of Latvia from the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union declared that "fascism was reborn in Latvia."[20]

In 2006, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) found contrary to the Article 10 (freedom of expression) of the ECHR fining a journalist for calling a right-wing journalist "local neo-fascist", regarding the statement as a value-judgment acceptable in the circumstances.[21]

During the Euromaidan demonstrations in January 2014, the Slavic Anti-Fascist Front was created in Crimea by Russian member of parliament Aleksey Zhuravlyov and Crimean Russian Unity party leader and future head of the Republic of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov to oppose "fascist uprising" in Ukraine.[22][23] After the February 2014 Ukrainian revolution, through the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation and the outbreak of the war in Donbass, Russian nationalists and state media used the term. They frequently described the Ukrainian government after Euromaidan as fascist or Nazi,[24][25] at the same time using antisemitic canards, such as accusing them of "Jewish influence", and stating that they were spreading "gay propaganda", a trope of anti-LGBT activism.[26]

In his 21 February speech, which started the events leading to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin falsely accused Ukraine of being governed by Neo-Nazis who persecute the ethnic Russian minority and Russian-speaking Ukrainians.[27][28] Putin's claims about "de-Nazification" have been widely described as absurd.[29] While Ukraine has a far-right fringe, including the neo-Nazi-linked Azov Battalion and Right Sector,[33] experts have described[34] Putin's rhetoric as greatly exaggerating the influence of far-right groups within Ukraine; there is no widespread support for the ideology in the government, military, or electorate.[35][36][37] Russian far-right organizations also exist, such as the Russian Imperial Movement, long active in Donbas.[41] Ukrainian president Zelenskyy, who is Jewish, rebuked Putin's allegations, stating that his grandfather had served in the Soviet army fighting against the Nazis.[42] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem condemned the abuse of Holocaust history and the use of comparisons with Nazi ideology for propaganda.[43][44]

Several Ukrainian politicians, military leader and members of the Ukrainian civil society have also accused the Russian Federation of being a fascist country.[45][46][47] Ukrainian propaganda also compares Vladimir Putin to Adolf Hitler, calling him a "Putler," and Russian troops to the Nazis, calling them a mixture of Russians and fascists, "ruscists."[34]

Serbia

[edit]During the 1990s, in the midst of the Yugoslav wars, Serbian media often disseminated inflammatory statements in order to stigmatize and dehumanize adversaries, with Croats being denigrated as "Ustasha" (Croatian fascists).[48] In modern Serbia, Dragan J. Vučićević, editor-in-chief of the tabloid and propaganda flagship Informer, holds the belief that the "vast majority of Croatian nation are Ustaše" and thus ''fascists''.[49][50] The same notion is sometimes drawn through his tabloid's writings.[49]

In 2019, after a Serbian armed forces delegation was barred from entering Croatia without prior state notice to visit Jasenovac concentration camp Memorial Site in their official uniforms, Aleksandar Vulin, the Serbian defense minister commented on the barred visit by saying that modern Croatia is a "follower of Ante Pavelić's fascist ideology." The Croatian authorities searched them and returned them to Serbia with the explanation that they cannot bring official uniforms into Croatia and that they do not have documents that justify the purpose of their stay in the country.[51][52][53] In June 2022, Aleksandar Vučić was prevented from entering Croatia to visit the Jasenovac Memorial Site by Croatian authorities due to him not announcing his visit through official diplomatic channels which is a common practice. As a response to that certain Serbian ministers labeled Andrej Plenković's government as "ustasha government" with some tabloids calling Croatia fascist. Historian Alexander Korb compared these labels with Putin's labels of Ukraine being fascist as a pretext for his invasion of Ukraine.[54][55][56] After the EU banned Serbia from importing Russian oil through Croatian Adriatic Pipeline in October 2022, Serbian news station B92 wrote that the sanctions came after: "insisting of ustasha regime from Zagreb and its ustasha prime minister Andrej Plenković".[57] Vulin described the EU as "the club of countries which had their divisions under Stalingrad".[58]

England

[edit]In 1944, the English writer, democratic socialist, and anti-fascist George Orwell wrote about the term's overuse as an epithet, arguing:

It will be seen that, as used, the word 'Fascism' is almost entirely meaningless. In conversation, of course, it is used even more wildly than in print. I have heard it applied to farmers, shopkeepers, Social Credit, corporal punishment, fox-hunting, bull-fighting, the 1922 Committee, the 1941 Committee, Kipling, Gandhi, Chiang Kai-Shek, homosexuality, Priestley's broadcasts, Youth Hostels, astrology, women, dogs and I do not know what else. ... [T]he people who recklessly fling the word 'Fascist' in every direction attach at any rate an emotional significance to it. By 'Fascism' they mean, roughly speaking, something cruel, unscrupulous, arrogant, obscurantist, anti-liberal and anti-working-class. Except for the relatively small number of Fascist sympathizers, almost any English person would accept 'bully' as a synonym for 'Fascist'. That is about as near to a definition as this much-abused word has come.[59]

Historian Stanley G. Payne argues that after World War II, fascism assumed a quasi-religious position within Western culture as a form of absolute moral evil. This gives its use as an epithet a particularly strong form of social power that any other equivalent term lacks, which Payne argues encourages its overuse as it offers an extremely easy way to stigmatize and assert power over an opponent.[60]

United States

[edit]In the United States, fascist is used by both the left-wing and right-wing, and its use in American political discourse is contentious. Several U.S. presidencies have been described as fascistic. In 2004, Samantha Power, a lecturer at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, reflected Orwell's words from 60 years prior when she stated: "Fascism – unlike communism, socialism, capitalism, or conservatism – is a smear word more often used to brand one's foes than it is a descriptor used to shed light on them."[61]

Conservative use

[edit]In the American right wing, fascist is frequently used as an insult to imply that Nazism, and by extension fascism, was a socialist and left-wing ideology, which is contrary to the consensus among scholars of fascism.[5] According to the History News Network, this belief that fascism is left-wing "has become widely accepted conventional wisdom among American conservatives, and has played a significant role in the national discourse."[62] According to cultural critic Noah Berlatsky writing for NBC News, in an effort to erase leftist victims of Nazi violence, "they've actually inverted the truth, implying that Nazis themselves were leftists", and "are part of a history of far-right disavowal, projection and escalation intended to provide a rationale for retaliation."[63]

An example of this belief is conservative columnist Jonah Goldberg's book Liberal Fascism, which depicts modern liberalism and progressivism in the United States as the children of fascism. Writing for The Washington Post, historian Ronald J. Granieri stated that this "has become a silver bullet for voices on the right like Dinesh D'Souza and Candace Owens: Not only is the reviled left, embodied in 2020 by figures like Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Elizabeth Warren, a dangerous descendant of the Nazis, but anyone who opposes it can't possibly have ties to the Nazis' odious ideas. There is only one problem: This argument is untrue."[5] Other examples include statements by Republican Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, who has compared mask mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic to Nazi Germany and the Holocaust.[63]

Use by the left

[edit]In the 1980s, the term was used by leftist critics to describe the presidency of Ronald Reagan. The term was later used in the 2000s to describe the presidency of George W. Bush by its critics and in the late 2010s to describe the candidacy and presidency of Donald Trump. In her 1970 book Beyond Mere Obedience, radical activist and theologian Dorothee Sölle coined the term Christofascist to describe fundamentalist Christians.[64][65][66]

In response to multiple authors claiming that the then-presidential candidate Donald Trump was a fascist,[67][68][69][70] a 2016 article for Vox cited five historians who study fascism, including Roger Griffin, author of The Nature of Fascism, who stated that Trump either does not hold and even is opposed to several political viewpoints that are integral to fascism, including viewing violence as an inherent good and an inherent rejection of or opposition to a democratic system.[71]

A growing number of scholars have posited that the political style of Trump resembles that of fascist leaders, beginning with his election campaign in 2016,[72][73] continuing over the course of his presidency as he appeared to court far-right extremists,[74][75][76][77] including his failed efforts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election results after losing to Joe Biden,[78] and culminating in the 2021 United States Capitol attack.[79] As these events have unfolded, some commentators who had initially resisted applying the label to Trump came out in favor of it, including conservative legal scholar Steven G. Calabresi[80] and conservative commentator Michael Gerson.[81] After the attack on the Capitol, the historian of fascism Robert O. Paxton went so far as to state that Trump is a fascist, despite his earlier objection to using the term in this way.[82] Other historians of fascism such as Richard J. Evans,[83] Griffin, and Stanley Payne continue to disagree that fascism is an appropriate term to describe Trump's politics.[79]

Chile

[edit]In Chile, the insult facho pobre ("poor fascist" or "low-class fascist") is used against people of perceived working class status with right-leaning views, is the equivalent to class traitor or lumpenproletariat, and it has been the subject of significant analysis, including by figures such as the sociologist Alberto Mayol and political commentator Carlos Peña González.[84][85] The origin of the insult can possibly be traced back to the massive use in Chile of social networks and their use in political discussions, but was popularized in the aftermath of the 2017 Chilean general election, where right-wing Sebastián Piñera won the presidency with a strong working class voter base.[86] Peña González calls the essence of the insult "the worst of the paternalisms: the belief that ordinary people ... do not know what they want and betray their true interest at the time of choice",[86] while writer Oscar Contardo states that the insult is a sort of "left-wing classism" (Spanish: roteo de izquierda) and implies that "certain ideas can only be defended by the priviledged class."[84]

In 2019, left-wing deputy and future President Gabriel Boric publicly criticized the phrase facho pobre as belonging to an "elitist left", and warned that its use may lead to political isolation.[87]

Israel–Hamas war

[edit]During the Israel-Hamas war, the state of Israel has been called fascist. For instance, on October 11 2024, Nicaragua broke off relations with Israel calling the Israeli government "fascist" and "genocidal."[88]

See also

[edit]- Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire

- Definitions of fascism

- Godwin's law

- Nazi analogies

- Political insult

- Red-baiting

- Red fascism

- Reductio ad Hitlerum

- Social fascism

References

[edit]- ^ Haro, Lea (2011). "Entering a Theoretical Void: The Theory of Social Fascism and Stalinism in the German Communist Party". Critique: Journal of Socialist Theory. 39 (4): 563–582. doi:10.1080/03017605.2011.621248. S2CID 146848013.

- ^ Adelheid von Saldern, The Challenge of Modernity: German Social and Cultural Studies, 1890-1960 (2002), University of Michigan Press, p. 78, ISBN 0-472-10986-3.

- ^ "Editorial: The Russian Betrayal". The New York Times. 18 September 1939.

- ^ Orwell, George (1944). "What is Fascism?". Tribune.

- ^ a b c Granieri, Ronald J. (5 February 2020). "The right needs to stop falsely claiming that the Nazis were socialists". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Agethen, Manfred; Jesse, Eckhard; Neubert, Ehrhart (2002). Der missbrauchte Antifaschismus. Freiburg: Verlag Herder. ISBN 978-3451280177.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2008). Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Pan Macmillan. p. 54. ISBN 9780330472296.

- ^ a b c Adler, Les K.; Paterson, Thomas G. (April 1970). "Red Fascism: The Merger of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the American Image of Totalitarianism, 1930s–1950s". The American Historical Review. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 75 (4): 1046–1064. doi:10.2307/1852269. JSTOR 1852269.

- ^ Draper, Theodore (February 1969). "The Ghost of Social-Fascism". Commentary: 29–42.

- ^ "Наступление фашизма и задачи Коммунистического Интернационала в борьбе за единство рабочего класса против фашизма". 7th Comintern Congress. 20 August 1935. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ "Фашизм – наиболее мрачное порождение империализма". История второй мировой войны 1939–1945 гг. 1973. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Robert Stiller, "Semantyka zbrodni"

- ^ "1944 – Powstanie Warszawskie". e-Warszawa.com. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ Maciej Gelberg, "Wierni do końca" [w:] "Kombatant", nr 3 (291), Urząd do spraw Kombatantów i Osób Represjonowanych, Warszawa 2015, s.10

- ^ "Dane osoby z katalogu funkcjonariuszy aparatu bezpieczeństwa – Franciszek Przeździał". Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. 1951. Archived from the original on November 20, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- ^ Kendall, Bridget (6 July 2017). The Cold War: A New Oral History of Life Between East and West. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-3087-4 – via Google Books.

- ^ Fryer, Peter (1957). "The Second Soviet Intervention". Hungarian Tragedy. London: D. Dobson. ASIN B0007J7674. Archived from the original on 1 December 2006 – via Vorhaug.net.

- ^ "Goethe-Institut – Topics – German-German History Goethe-Institut". 9 April 2008. Archived from the original on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ Rea, Kenneth W. (1975). "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1080/00927678.1975.10554159. ISSN 0092-7678. JSTOR 30171400 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga".

- ^ "Case of Karman v. Russia (Application no. 29372/02) Judgment". European Court of Human Rights. 14 March 2007.

- ^ Shynkarenko, Oleg (18 February 2014). "The Battle for Kiev Begins". Daily Beast. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Elizabeth A. Wood (2015). Roots of Russia's War in Ukraine. Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

- ^ Shuster, Simon (20 October 2014). "Russians Re-write History to Slur Ukraine Over War". Time. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (20 March 2014). "Fascism, Russia, and Ukraine". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Wagstyl, Stefan. "Fascism: a useful insult". Financial Times.

- ^ Finkel, Eugene; Tabarovsky, Izabella (27 February 2022). "Statement on the War in Ukraine by Scholars of Genocide, Nazism and World War II". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles.

- ^ "Putin says he is fighting a resurgence of Nazism. That's not true". NBC News. 24 February 2022.

- ^ Stanley, Jason (26 February 2022). "The antisemitism animating Putin's claim to 'denazify' Ukraine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Berger, Miriam (24 February 2022). "Russian President Valdimir Putin says he will 'denazify' Ukraine. Here's the history behind that claim". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Campbell, Eric (3 March 2022). "Inside Donetsk, the separatist republic that triggered the war in Ukraine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Schipani, Andres; Olearchyk, Roman (29 March 2022). "'Don't confuse patriotism and Nazism': Ukraine's Azov forces face scrutiny". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ [30][31][32]

- ^ a b Cain Burdeau (26 April 2022). "Russia warns of World War III, West boosts arms to Ukraine". Courthouse News Service. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Li, David K.; Allen, Jonathan; Siemaszko, Corky (24 February 2022). "Putin using false 'Nazi' narrative to justify Russia's attack on Ukraine, experts say". NBC News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Abbruzzese, Jason (24 February 2022). "Putin says he is fighting a resurgence of Nazism. That's not true". NBC News. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The Azov Battalion: How Putin built a false premise for a war against "Nazis" in Ukraine". CBS News. 22 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Shekhovtsov, Anton (13 April 2022). "The Shocking Inspiration for Russia's Atrocities in Ukraine". Haaretz. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ "Neo-Nazi Russian nationalist exposes how Russia's leaders sent them to Ukraine to kill Ukrainians". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Horvath, Robert (21 March 2022). "Putin's fascists: the Russian state's long history of cultivating homegrown neo-Nazis". The Conversation. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ [38][39][40]

- ^ Lawler, Dave; Basu, Zachary (24 February 2022). "Ukrainian President Zelensky says Putin has ordered invasion as country prepares for war". Axios. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy. "Putin's Hitler-like tricks and tactics in Ukraine". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Yad Vashem Statement Regarding the Russian Invasion of Ukraine" (Press release). Yad Vashem. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Рашисти готуються відновити наступ у напрямку Києва: як минула доба на фронті. glavcom.ua (in Ukrainian). 14 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Рашисти будуть вигнані з нашої землі": Ігор Кондратюк підтримав ЗСУ. www.unian.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Рашисти влаштували бомбардування території Білорусі. Defense Express (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ de la Brosse, Renaud. "Political Propaganda and the Plan to Create a "State for all Serbs": Consequences of Using the Media for Ultra-nationalist Ends" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2005. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

Certain key words would be used over and over again to stir up a defensive reaction among the Serbian citizens who would support the government's plan to create a State for all Serbs. For example, the terms "Ustasha fascists" "and cut-throats" were used to stigmatise the Croats and "Islamic ustasha" and "jihad fighters" to describe Bosnian Muslims pejoratively... Through reports and commentaries intervowen with images, television sought to foster inter-ethnic and religious hatred towards the Cahtolic Croatian community: general opinion portrayed them as inhuman - thereby making their humiliation, destruction and hreasier and more legitimate.

- ^ a b "Kako Informerova matematika "dokazuje" da su skoro svi Hrvati ustaše". Raskrikavanje (in Serbo-Croatian). Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Tomičić, Ladislav (6 February 2017). "Razgovor s vlasnikom Informera, najzloćudnijeg tabloida Balkana: Vučićeviću, jeste li vi budala?". Novi list (in Croatian). euroart. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Vučić i Vulin napali Hrvatsku zbog zabrane srpskim vojnicima da idu u Jasenovac". www.index.hr (in Croatian).

- ^ "Vulin o zabrani ulaska: Hrvatska je sljedbenica fašističke Pavelićeve ideologije". Radiosarajevo.ba (in Bosnian). Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ "Ravnatelj policije otkrio zašto izaslanstvo Vojske Srbije nije moglo ući u Hrvatsku, oglasio se i Vučić". Dnevnik.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ Stojanovic, Milica (18 July 2022). "Serbian Tabloids Call Croatia 'Fascist' for Preventing Vucic Visit". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Slobodna Dalmacija - Njemački povjesničar 'ošinuo' po Vučiću: On se morao najaviti Hrvatskoj, ovo što tvrdi je farsa. Ali on je zadovoljan, ostvario je svoj cilj i iskoristio žrtve Jasenovca..." slobodnadalmacija.hr (in Croatian). 19 July 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Matić, Srećko (19 July 2022). "Njemački povjesničar: "Kalkulirana provokacija Aleksandra Vučića"". DW.COM (in Croatian). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Hrvatska na čelu sa Plenkovićem stopirala uvoz ruske nafte u Srbiju preko Janafa". B92.net (in Serbian). 10 June 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

Na insistiranje ustaškog režima u Hrvatskoj na čelu sa premijerom te zemlje Andrejem Plenkovićem, taj paket obuhvatiće i Srbiju jer preko Janafa neće moći više da uvozi rusku naftu.

- ^ "Vulin: Ako su pakosti ustaša stavovi EU, onda je Milov plaćenik Picula lice EU". N1 (in Croatian). 13 October 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Rosman, Artur Sebastian (February 19, 2019). "Orwell Watch #27: What is fascism? Does anybody know?" Stanford University. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Payne, Stanley (22 January 2021). "Antifascism without Fascism". First Things. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ Power, Samantha (May 2, 2014). "The Original Axis of Evil". The New York Times. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Introduction". Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b Berlatsky, Noah (8 July 2021). "Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene can't stop making Covid-Nazi comparisons". NBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Dorothee Sölle (1970). Beyond Mere Obedience: Reflections on a Christian Ethic for the Future. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House.

- ^ "Confessing Christ in a Post-Christendom Context". The Ecumenical Review. 1 July 2000. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

... shall we say this, represent this, live this, without seeming to endorse the kind of christomonism (Dorothee Solle called it 'Christofascism'! ...

[permanent dead link] - ^ Pinnock, Sarah K. (2003). The Theology of Dorothee Soelle. Trinity Press International. ISBN 1-56338-404-3.

... of establishing a dubious moral superiority to justify organized violence on a massive scale, a perversion of Christianity she called Christofascism. ...

- ^ "'Racist', 'fascist', 'utterly repellent': What the world said about Donald Trump". BBC News. 9 December 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Gopnik, Adam (11 May 2016). "Going There with Donald Trump". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Swift, Nathan (26 October 2015). "Donald Trump's fascist tendencies". The Highlander. Highlander Newspaper. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Hodges, Dan (9 December 2015). "Donald Trump is an outright fascist who should be banned from Britain today". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (19 May 2016). "I asked 5 fascism experts whether Donald Trump is a fascist. Here's what they said". Vox. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Kagan, Robert (18 May 2016). "This is how fascism comes to America". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ McGaughey, Ewan (2018). "Fascism-Lite in America (or the Social Ideal of Donald Trump)". British Journal of American Legal Studies. 7 (2): 291–315. doi:10.2478/bjals-2018-0012. S2CID 195842347. SSRN 2773217.

- ^ Stanley, Jason (15 October 2018). "If You're Not Scared About Fascism in the U.S., You Should Be". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (30 October 2018). "Donald Trump borrows from the old tricks of fascism". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Peter (7 January 2020). "Why Historical Analogy Matters". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Szalai, Jennifer (10 June 2020). "The Debate Over the Word Fascism Takes a New Turn". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Cummings, William; Garrison, Joey; Sergent, Jim (6 January 2021). "By the numbers: President Donald Trump's failed efforts to overturn the election". USA Today. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b Matthews, Dylan (14 January 2020). "The F Word: The debate over whether to call Donald Trump a fascist, and why it matters". Vox. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Calabresi, Steven G. (20 July 2020). "Trump Might Try to Postpone the Election. That's Unconstitutional". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Gerson, Michael (1 February 2021). "Trumpism is American fascism". The Washington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Paxton, Robert O. (11 January 2021). "I've Hesitated to Call Donald Trump a Fascist. Until Now". Newsweek. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (13 January 2021). "Why Trump isn't a fascist". The New Statesman. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b "¿Qué es ser un facho pobre?". The Clinic (in Spanish). 15 November 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Carlos Peña y el concepto de 'facho pobre': 'Los insultos a la gente que votó a la derecha revelan una grave incomprensión'". El Desconcierto (in Spanish). 31 December 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b Peña, Carlos (31 December 2017). "Facho pobre". El Mercurio.

- ^ Jaime (24 November 2021). "Boric dedica frase a la "izquierda élite" que tilda de "fachos pobres" a los votantes de Piñera". Radio San Joaquín (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/nicaragua-breaks-diplomatic-relations-with-israel-2024-10-11/

External links

[edit]- Masso, Iivi (19 February 2009). "Fašism kui propaganda tööriist". (Fascism as a tool of propaganda). Eesti Päevaleht. Retrieved 16 August 2021.