Ottoman Empire

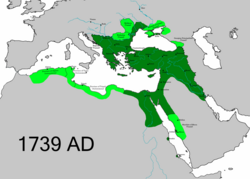

The Ottoman Empire,[j] historically and colloquially known as the Turkish Empire,[24][25] was an empire[k] centred in Anatolia that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Central Europe between the early 16th and early 18th centuries.[26][27][28]

The empire emerged from a beylik, or principality, founded in northwestern Anatolia in 1299 by the Turkoman tribal leader Osman I. His successors conquered much of Anatolia and expanded into the Balkans by the mid-14th century, transforming their petty kingdom into a transcontinental empire. The Byzantine Empire was ended with the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 under the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II, which marked the Ottomans' emergence as a major regional power. Under Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566), the empire reached the peak of its power, prosperity, and political development. By the start of the 17th century, the Ottomans presided over 32 provinces and numerous vassal states, which over time were either absorbed into the Empire or granted various degrees of autonomy.[l] With its capital at Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) and control over a significant portion of the Mediterranean Basin, the Ottoman Empire was at the centre of interactions between the Middle East and Europe for six centuries.

While the Ottoman Empire was once thought to have entered a period of decline after the death of Suleiman the Magnificent, modern academic consensus posits that the empire continued to maintain a flexible and strong economy, society and military into much of the 18th century. However, during a long period of peace from 1740 to 1768, the Ottoman military system fell behind those of its chief European rivals, the Habsburg and Russian empires. The Ottomans consequently suffered severe military defeats in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, culminating in the loss of both territory and global prestige. This prompted a comprehensive process of reform and modernization known as the Tanzimat; over the course of the 19th century, the Ottoman state became vastly more powerful and organized internally, despite suffering further territorial losses, especially in the Balkans, where a number of new states emerged.

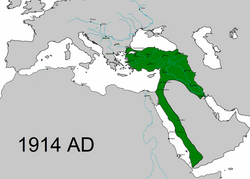

Beginning in the late 19th century, various Ottoman intellectuals sought to further liberalize society and politics along European lines, culminating in the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which established the Second Constitutional Era and introduced competitive multi-party elections under a constitutional monarchy. However, following the disastrous Balkan Wars, the CUP became increasingly radicalized and nationalistic, leading a coup d'état in 1913 that established a one-party regime. The CUP allied with the German Empire hoping to escape from the diplomatic isolation that had contributed to its recent territorial losses; it thus joined World War I on the side of the Central Powers. While the empire was able to largely hold its own during the conflict, it struggled with internal dissent, especially the Arab Revolt. During this period, the Ottoman government engaged in genocide against Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks.

In the aftermath of World War I, the victorious Allied Powers occupied and partitioned the Ottoman Empire, which lost its southern territories to the United Kingdom and France. The successful Turkish War of Independence, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk against the occupying Allies, led to the emergence of the Republic of Turkey in the Anatolian heartland and the abolition of the Ottoman monarchy in 1922, formally ending the Ottoman Empire.

Name

The word Ottoman is a historical anglicisation of the name of Osman I, the founder of the Empire and of the ruling House of Osman (also known as the Ottoman dynasty). Osman's name in turn was the Turkish form of the Arabic name ʿUthmān (عثمان). In Ottoman Turkish, the empire was referred to as Devlet-i ʿAlīye-yi ʿOsmānīye (دولت عليه عثمانیه), lit. 'Sublime Ottoman State', or simply Devlet-i ʿOsmānīye (دولت عثمانيه), lit. 'Ottoman State'.[citation needed]

The Turkish word for "Ottoman" (Osmanlı) originally referred to the tribal followers of Osman in the fourteenth century. The word subsequently came to be used to refer to the empire's military-administrative elite. In contrast, the term "Turk" (Türk) was used to refer to the Anatolian peasant and tribal population and was seen as a disparaging term when applied to urban, educated individuals.[30][31] In the early modern period, an educated, urban-dwelling Turkish speaker who was not a member of the military-administrative class typically referred to themselves neither as an Osmanlı nor as a Türk, but rather as a Rūmī (رومى), or "Roman", meaning an inhabitant of the territory of the former Byzantine Empire in the Balkans and Anatolia. The term Rūmī was also used to refer to Turkish speakers by the other Muslim peoples of the empire and beyond.[32] As applied to Ottoman Turkish speakers, this term began to fall out of use at the end of the seventeenth century, and instead the word increasingly became associated with the Greek population of the empire, a meaning that it still bears in Turkey today.[33]

In Western Europe, the names Ottoman Empire, Turkish Empire and Turkey were often used interchangeably, with Turkey being increasingly favoured both in formal and informal situations. This dichotomy was officially ended in 1920–1923, when the newly established Ankara-based Turkish government chose Turkey as the sole official name. According to Svat Soucek, most scholarly historians at present avoid the terms "Turkey", "Turks", and "Turkish" when referring to the Ottomans, due to the empire's multinational character.[34]

History

| History of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

.svg/125px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_Ottoman_Empire_(1882–1922).svg.png) |

| Timeline |

| Historiography (Ghaza, Decline) |

The Ottoman Empire was founded c. 1299 by Osman I as a small beylik in northwestern Asia Minor just south of the Byzantine capital Constantinople. In 1326, the Ottomans captured nearby Bursa, cutting off Asia Minor from Byzantine control. The Ottomans first crossed into Europe in 1352, establishing a permanent settlement at Çimpe Castle on the Dardanelles in 1354 and moving their capital to Edirne (Adrianople) in 1369. At the same time, the numerous small Turkic states in Asia Minor were assimilated into the budding Ottoman sultanate through conquest or declarations of allegiance.

As Sultan Mehmed II conquered Constantinople (today named Istanbul) in 1453, transforming it into the new Ottoman capital, the state grew into a substantial empire, expanding deep into Europe, northern Africa and the Middle East. With most of the Balkans under Ottoman rule by the mid-16th century, Ottoman territory increased exponentially under Sultan Selim I, who assumed the Caliphate in 1517 as the Ottomans turned east and conquered western Arabia, Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Levant, among other territories. Within the next few decades, much of the North African coast (except Morocco) became part of the Ottoman realm.

The empire reached its apex under Suleiman the Magnificent in the 16th century, when it stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to Algeria in the west, and from Yemen in the south to Hungary and parts of Ukraine in the north. According to the Ottoman decline thesis, Suleiman's reign was the zenith of the Ottoman classical period, during which Ottoman culture, arts, and political influence flourished. The empire reached its maximum territorial extent in 1683, on the eve of the Battle of Vienna.

From 1699 onwards, the Ottoman Empire began to lose territory over the course of the next two centuries due to internal stagnation, costly defensive wars, European colonialism, and nationalist revolts among its multiethnic subjects. In any case, the need to modernise was evident to the empire's leaders by the early 19th century, and numerous administrative reforms were implemented in an attempt to forestall the decline of the empire, with varying degrees of success. The gradual weakening of the Ottoman Empire gave rise to the Eastern Question in the mid-19th century.

The empire came to an end in the aftermath of its defeat in World War I, when its remaining territory was partitioned by the Allies. The sultanate was officially abolished by the Government of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara on 1 November 1922 following the Turkish War of Independence. Throughout its more than 600 years of existence, the Ottoman Empire has left a profound legacy in the Middle East and Southeast Europe, as can be seen in the customs, culture, and cuisine of the various countries that were once part of its realm.

Historiographical debate on the Ottoman state

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Several historians, such as British historian Edward Gibbon and the Greek historian Dimitri Kitsikis, have argued that after the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman state took over the machinery of the Byzantine (Roman) state and that the Ottoman Empire was in essence a continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire under a Turkish Muslim guise.[35] The American historian Speros Vryonis writes that the Ottoman state centred on "a Byzantine-Balkan base with a veneer of the Turkish language and the Islamic religion".[36] Kitsikis and the American historian Heath Lowry posit that the early Ottoman state was a predatory confederacy open to both Byzantine Christians and Turkish Muslims whose primary goal was attaining booty and slaves, rather than spreading Islam, and that Islam only later became the empire's primary characteristic.[37][38][39] Other historians have followed the lead of the Austrian historian Paul Wittek, who emphasizes the early Ottoman state's Islamic character, seeing it as a "jihad state" dedicated to expanding the Muslim world.[36] Many historians led in 1937 by the Turkish historian Mehmet Fuat Köprülü championed the Ghaza thesis, according to which the early Ottoman state was a continuation of the way of life of the nomadic Turkic tribes who had come from East Asia to Anatolia via Central Asia and the Middle East on a much larger scale. They argued that the most important cultural influences on the Ottoman state came from Persia.[40]

The British historian Norman Stone suggests many continuities between the Eastern Roman and Ottoman empires, such as that the zeugarion tax of Byzantium became the Ottoman Resm-i çift tax, that the pronoia land-holding system that linked the amount of land one owned with one's ability to raise cavalry became the Ottoman timar system, and that the Ottoman land measurement the dönüm was the same as the Byzantine stremma. Stone also argues that although Sunni Islam was the state religion, the Ottoman state supported and controlled the Eastern Orthodox Church, which in return for accepting that control became the Ottoman Empire's largest land-holder. Despite the similarities, Stone argues that a crucial difference is that the land grants under the timar system were not hereditary at first. Even after they became inheritable, land ownership in the Ottoman Empire remained highly insecure, and the sultan revoked land grants whenever he wished. Stone argued this insecurity in land tenure strongly discouraged Timariots from seeking long-term development of their land, and instead led them to adopt a strategy of short-term exploitation, which had deleterious effects on the Ottoman economy.[41]

Government

Before the reforms of the 19th and 20th centuries, the state organisation of the Ottoman Empire was a system with two main dimensions: the military administration and the civil administration. The Sultan was the highest position in the system. The civil system was based on local administrative units based on the region's characteristics. The state had control over the clergy. Certain pre-Islamic Turkish traditions that had survived the adoption of administrative and legal practices from Islamic Iran remained important in Ottoman administrative circles.[44] According to Ottoman understanding, the state's primary responsibility was to defend and extend the land of the Muslims and to ensure security and harmony within its borders in the overarching context of orthodox Islamic practice and dynastic sovereignty.[45]

The Ottoman Empire, or, as a dynastic institution, the House of Osman, was unprecedented and unequaled in the Islamic world for its size and duration.[46] In Europe, only the House of Habsburg had a similarly unbroken line of sovereigns (kings/emperors) from the same family who ruled for so long, and during the same period, between the late 13th and early 20th centuries. The Ottoman dynasty was Turkish in origin. On eleven occasions, the sultan was deposed (replaced by another sultan of the Ottoman dynasty, who were either the former sultan's brother, son or nephew) because he was perceived by his enemies as a threat to the state. There were only two attempts in Ottoman history to unseat the ruling Ottoman dynasty, both failures, which suggests a political system that for an extended period was able to manage its revolutions without unnecessary instability.[45] As such, the last Ottoman sultan Mehmed VI (r. 1918–1922) was a direct patrilineal (male-line) descendant of the first Ottoman sultan Osman I (d. 1323/4), which was unparalleled in both Europe (e.g., the male line of the House of Habsburg became extinct in 1740) and in the Islamic world. The primary purpose of the Imperial Harem was to ensure the birth of male heirs to the Ottoman throne and secure the continuation of the direct patrilineal power of the Ottoman sultans in the future generations.[citation needed]

The highest position in Islam, caliph, was claimed by the sultans starting with Selim I,[18] which was established as the Ottoman Caliphate. The Ottoman sultan, pâdişâh or "lord of kings", served as the Empire's sole regent and was considered to be the embodiment of its government, though he did not always exercise complete control. The Imperial Harem was one of the most important powers of the Ottoman court. It was ruled by the valide sultan. On occasion, the valide sultan became involved in state politics. For a time, the women of the Harem effectively controlled the state in what was termed the "Sultanate of Women". New sultans were always chosen from the sons of the previous sultan.[dubious – discuss] The strong educational system of the palace school was geared towards eliminating the unfit potential heirs and establishing support among the ruling elite for a successor. The palace schools, which also educated the future administrators of the state, were not a single track. First, the Madrasa (Medrese) was designated for the Muslims, and educated scholars and state officials according to Islamic tradition. The financial burden of the Medrese was supported by vakifs, allowing children of poor families to move to higher social levels and income.[47] The second track was a free boarding school for the Christians, the Enderûn,[48] which recruited 3,000 students annually from Christian boys between eight and twenty years old from one in forty families among the communities settled in Rumelia or the Balkans, a process known as Devshirme (Devşirme).[49]

Though the sultan was the supreme monarch, the sultan's political and executive authority was delegated. The politics of the state had a number of advisors and ministers gathered around a council known as Divan. The Divan, in the years when the Ottoman state was still a Beylik, was composed of the elders of the tribe. Its composition was later modified to include military officers and local elites (such as religious and political advisors). Later still, beginning in 1320, a Grand Vizier was appointed to assume certain of the sultan's responsibilities. The Grand Vizier had considerable independence from the sultan with almost unlimited powers of appointment, dismissal, and supervision. Beginning with the late 16th century, sultans withdrew from politics and the Grand Vizier became the de facto head of state.[50]

Throughout Ottoman history, there were many instances in which local governors acted independently, and even in opposition to the ruler. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, the Ottoman state became a constitutional monarchy. The sultan no longer had executive powers. A parliament was formed, with representatives chosen from the provinces. The representatives formed the Imperial Government of the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed]

This eclectic administration was apparent even in the diplomatic correspondence of the Empire, which was initially undertaken in the Greek language to the west.[51]

The Tughra were calligraphic monograms, or signatures, of the Ottoman Sultans, of which there were 35. Carved on the Sultan's seal, they bore the names of the Sultan and his father. The statement and prayer, "ever victorious", was also present in most. The earliest belonged to Orhan Gazi. The ornately stylized Tughra spawned a branch of Ottoman-Turkish calligraphy.[citation needed]

Law

The Ottoman legal system accepted the religious law over its subjects. At the same time the Qanun (or Kanun), dynastic law, co-existed with religious law or Sharia.[53][54] The Ottoman Empire was always organized around a system of local jurisprudence. Legal administration in the Ottoman Empire was part of a larger scheme of balancing central and local authority.[55] Ottoman power revolved crucially around the administration of the rights to land, which gave a space for the local authority to develop the needs of the local millet.[55] The jurisdictional complexity of the Ottoman Empire was aimed to permit the integration of culturally and religiously different groups.[55] The Ottoman system had three court systems: one for Muslims, one for non-Muslims, involving appointed Jews and Christians ruling over their respective religious communities, and the "trade court". The entire system was regulated from above by means of the administrative Qanun, i.e., laws, a system based upon the Turkic Yassa and Töre, which were developed in the pre-Islamic era.[56][57]

These court categories were not, however, wholly exclusive; for instance, the Islamic courts, which were the Empire's primary courts, could also be used to settle a trade conflict or disputes between litigants of differing religions, and Jews and Christians often went to them to obtain a more forceful ruling on an issue. The Ottoman state tended not to interfere with non-Muslim religious law systems, despite legally having a voice to do so through local governors. The Islamic Sharia law system had been developed from a combination of the Qur'an; the Hadīth, or words of Muhammad; ijmā', or consensus of the members of the Muslim community; qiyas, a system of analogical reasoning from earlier precedents; and local customs. Both systems were taught at the Empire's law schools, which were in Istanbul and Bursa.[citation needed]

The Ottoman Islamic legal system was set up differently from traditional European courts. Presiding over Islamic courts was a Qadi, or judge. Since the closing of the ijtihad, or 'Gate of Interpretation', Qadis throughout the Ottoman Empire focused less on legal precedent, and more with local customs and traditions in the areas that they administered.[55] However, the Ottoman court system lacked an appellate structure, leading to jurisdictional case strategies where plaintiffs could take their disputes from one court system to another until they achieved a ruling that was in their favour.[citation needed]

In the late 19th century, the Ottoman legal system saw substantial reform. This process of legal modernisation began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839.[58] These reforms included the "fair and public trial[s] of all accused regardless of religion", the creation of a system of "separate competences, religious and civil", and the validation of testimony on non-Muslims.[59] Specific land codes (1858), civil codes (1869–1876), and a code of civil procedure also were enacted.[59]

These reforms were based heavily on French models, as indicated by the adoption of a three-tiered court system. Referred to as Nizamiye, this system was extended to the local magistrate level with the final promulgation of the Mecelle, a civil code that regulated marriage, divorce, alimony, will, and other matters of personal status.[59] In an attempt to clarify the division of judicial competences, an administrative council laid down that religious matters were to be handled by religious courts, and statute matters were to be handled by the Nizamiye courts.[59]

Military

The first military unit of the Ottoman State was an army that was organized by Osman I from the tribesmen inhabiting the hills of western Anatolia in the late 13th century. The military system became an intricate organization with the advance of the Empire. The Ottoman military was a complex system of recruiting and fief-holding. The main corps of the Ottoman Army included Janissary, Sipahi, Akıncı and Mehterân. The Ottoman army was once among the most advanced fighting forces in the world, being one of the first to use muskets and cannons. The Ottoman Turks began using falconets, which were short but wide cannons, during the Siege of Constantinople. The Ottoman cavalry depended on high speed and mobility rather than heavy armor, using bows and short swords on fast Turkoman and Arabian horses (progenitors of the Thoroughbred racing horse),[60][61] and often applied tactics similar to those of the Mongol Empire, such as pretending to retreat while surrounding the enemy forces inside a crescent-shaped formation and then making the real attack. The Ottoman army continued to be an effective fighting force throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries,[62][63] falling behind the empire's European rivals only during a long period of peace from 1740 to 1768.[64]

The modernization of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century started with the military. In 1826 Sultan Mahmud II abolished the Janissary corps and established the modern Ottoman army. He named them as the Nizam-ı Cedid (New Order). The Ottoman army was also the first institution to hire foreign experts and send its officers for training in western European countries. Consequently, the Young Turks movement began when these relatively young and newly trained men returned with their education.[citation needed]

The Ottoman Navy vastly contributed to the expansion of the Empire's territories on the European continent. It initiated the conquest of North Africa, with the addition of Algeria and Egypt to the Ottoman Empire in 1517. Starting with the loss of Greece in 1821 and Algeria in 1830, Ottoman naval power and control over the Empire's distant overseas territories began to decline. Sultan Abdülaziz (reigned 1861–1876) attempted to reestablish a strong Ottoman navy, building the largest fleet after those of Britain and France. The shipyard at Barrow, England, built its first submarine in 1886 for the Ottoman Empire.[65]

However, the collapsing Ottoman economy could not sustain the fleet's strength for long. Sultan Abdülhamid II distrusted the admirals who sided with the reformist Midhat Pasha and claimed that the large and expensive fleet was of no use against the Russians during the Russo-Turkish War. He locked most of the fleet inside the Golden Horn, where the ships decayed for the next 30 years. Following the Young Turk Revolution in 1908, the Committee of Union and Progress sought to develop a strong Ottoman naval force. The Ottoman Navy Foundation was established in 1910 to buy new ships through public donations.[citation needed]

The establishment of Ottoman military aviation dates back to between June 1909 and July 1911.[66][67] The Ottoman Empire started preparing its first pilots and planes, and with the founding of the Aviation School (Tayyare Mektebi) in Yeşilköy on 3 July 1912, the Empire began to tutor its own flight officers. The founding of the Aviation School quickened advancement in the military aviation program, increased the number of enlisted persons within it, and gave the new pilots an active role in the Ottoman Army and Navy. In May 1913, the world's first specialized Reconnaissance Training Program was started by the Aviation School, and the first separate reconnaissance division was established.[citation needed] In June 1914 a new military academy, the Naval Aviation School (Bahriye Tayyare Mektebi) was founded. With the outbreak of World War I, the modernization process stopped abruptly. The Ottoman Aviation Squadrons fought on many fronts during World War I, from Galicia in the west to the Caucasus in the east and Yemen in the south.[citation needed]

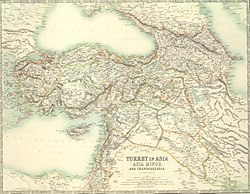

Administrative divisions

The Ottoman Empire was first subdivided into provinces, in the sense of fixed territorial units with governors appointed by the sultan, in the late 14th century.[68]

The Eyalet (also Pashalik or Beylerbeylik) was the territory of office of a Beylerbey ("lord of lords" or governor), and was further subdivided into Sanjaks.[69]

The Vilayets were introduced with the promulgation of the "Vilayet Law" (Teskil-i Vilayet Nizamnamesi)[70] in 1864, as part of the Tanzimat reforms.[71] Unlike the previous eyalet system, the 1864 law established a hierarchy of administrative units: the vilayet, liva/sanjak/mutasarrifate, kaza and village council, to which the 1871 Vilayet Law added the nahiye.[72]

Economy

.JPG/170px-AydınArchaeologicalMuseum_(117).JPG)

Ottoman government deliberately pursued a policy for the development of Bursa, Edirne, and Istanbul, successive Ottoman capitals, into major commercial and industrial centres, considering that merchants and artisans were indispensable in creating a new metropolis.[73] To this end, Mehmed and his successor Bayezid, also encouraged and welcomed migration of the Jews from different parts of Europe, who were settled in Istanbul and other port cities like Salonica. In many places in Europe, Jews were suffering persecution at the hands of their Christian counterparts, such as in Spain, after the conclusion of the Reconquista. The tolerance displayed by the Turks was welcomed by the immigrants.[citation needed]

.jpg/170px-Mehmed_the_Conqueror_(1432_–1481).jpg)

The Ottoman economic mind was closely related to the basic concepts of state and society in the Middle East in which the ultimate goal of a state was consolidation and extension of the ruler's power, and the way to reach it was to get rich resources of revenues by making the productive classes prosperous.[74] The ultimate aim was to increase the state revenues without damaging the prosperity of subjects to prevent the emergence of social disorder and to keep the traditional organization of the society intact. The Ottoman economy greatly expanded during the early modern period, with particularly high growth rates during the first half of the eighteenth century. The empire's annual income quadrupled between 1523 and 1748, adjusted for inflation.[75]

The organization of the treasury and chancery were developed under the Ottoman Empire more than any other Islamic government and, until the 17th century, they were the leading organization among all their contemporaries.[50] This organisation developed a scribal bureaucracy (known as "men of the pen") as a distinct group, partly highly trained ulama, which developed into a professional body.[50] The effectiveness of this professional financial body stands behind the success of many great Ottoman statesmen.[76]

Modern Ottoman studies indicate that the change in relations between the Ottoman Turks and central Europe was caused by the opening of the new sea routes. It is possible to see the decline in the significance of the land routes to the East as Western Europe opened the ocean routes that bypassed the Middle East and the Mediterranean as parallel to the decline of the Ottoman Empire itself.[77][failed verification] The Anglo-Ottoman Treaty, also known as the Treaty of Balta Liman that opened the Ottoman markets directly to English and French competitors, can be seen as one of the staging posts along with this development.[citation needed]

By developing commercial centres and routes, encouraging people to extend the area of cultivated land in the country and international trade through its dominions, the state performed basic economic functions in the Empire. But in all this, the financial and political interests of the state were dominant. Within the social and political system they were living in, Ottoman administrators could not see the desirability of the dynamics and principles of the capitalist and mercantile economies developing in Western Europe.[78]

Economic historian Paul Bairoch argues that free trade contributed to deindustrialisation in the Ottoman Empire. In contrast to the protectionism of China, Japan, and Spain, the Ottoman Empire had a liberal trade policy, open to foreign imports. This has origins in capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, dating back to the first commercial treaties signed with France in 1536 and taken further with capitulations in 1673 and 1740, which lowered duties to 3% for imports and exports. The liberal Ottoman policies were praised by British economists, such as John Ramsay McCulloch in his Dictionary of Commerce (1834), but later criticized by British politicians such as Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, who cited the Ottoman Empire as "an instance of the injury done by unrestrained competition" in the 1846 Corn Laws debate.[79]

Demographics

A population estimate for the empire of 11,692,480 for the 1520–1535 period was obtained by counting the households in Ottoman tithe registers, and multiplying this number by 5.[80] For unclear reasons, the population in the 18th century was lower than that in the 16th century.[81] An estimate of 7,230,660 for the first census held in 1831 is considered a serious undercount, as this census was meant only to register possible conscripts.[80]

Censuses of Ottoman territories only began in the early 19th century. Figures from 1831 onwards are available as official census results, but the censuses did not cover the whole population. For example, the 1831 census only counted men and did not cover the whole empire.[82][80] For earlier periods estimates of size and distribution of the population are based on observed demographic patterns.[83]

.jpg/220px-Bridge_and_Galata_Area%2C_Istanbul%2C_Turkey_by_Abdullah_Frères%2C_ca._1880-1893_(LOC).jpg)

However, it began to rise to reach 25–32 million by 1800, with around 10 million in the European provinces (primarily in the Balkans), 11 million in the Asiatic provinces, and around 3 million in the African provinces. Population densities were higher in the European provinces, double those in Anatolia, which in turn were triple the population densities of Iraq and Syria and five times the population density of Arabia.[84]

Towards the end of the empire's existence life expectancy was 49 years, compared to the mid-twenties in Serbia at the beginning of the 19th century.[85] Epidemic diseases and famine caused major disruption and demographic changes. In 1785 around one-sixth of the Egyptian population died from the plague and Aleppo saw its population reduced by twenty percent in the 18th century. Six famines hit Egypt alone between 1687 and 1731 and the last famine to hit Anatolia was four decades later.[86]

The rise of port cities saw the clustering of populations caused by the development of steamships and railroads. Urbanization increased from 1700 to 1922, with towns and cities growing. Improvements in health and sanitation made them more attractive to live and work in. Port cities like Salonica, in Greece, saw its population rise from 55,000 in 1800 to 160,000 in 1912 and İzmir which had a population of 150,000 in 1800 grew to 300,000 by 1914.[87][88] Some regions conversely had population falls—Belgrade saw its population drop from 25,000 to 8,000 mainly due to political strife.[87]

.jpg/220px-20180107_Safranbolu_1945_(39101010504).jpg)

Economic and political migrations made an impact across the empire. For example, the Russian and Austria-Habsburg annexation of the Crimean and Balkan regions respectively saw large influxes of Muslim refugees—200,000 Crimean Tartars fleeing to Dobruja.[89] Between 1783 and 1913, approximately 5–7 million refugees arrived into the Ottoman Empire. Between the 1850s and World War I, about a million North Caucasian Muslims arrived in the Ottoman Empire as refugees.[90] Some migrations left indelible marks such as political tension between parts of the empire (e.g., Turkey and Bulgaria), whereas centrifugal effects were noticed in other territories, simpler demographics emerging from diverse populations. Economies were also impacted by the loss of artisans, merchants, manufacturers, and agriculturists.[91] Since the 19th century, a large proportion of Muslim peoples from the Balkans emigrated to present-day Turkey. These people are called Muhacir.[92] By the time the Ottoman Empire came to an end in 1922, half of the urban population of Turkey was descended from Muslim refugees from Russia.[93]

Language

Ottoman Turkish was the official language of the Empire.[94] It was an Oghuz Turkic language highly influenced by Persian and Arabic, though lower registries spoken by the common people had fewer influences from other languages compared to higher varieties used by upper classes and governmental authorities.[95] Turkish, in its Ottoman variation, was a language of military and administration since the nascent days of the Ottomans. The Ottoman constitution of 1876 did officially cement the official imperial status of Turkish.[96]

The Ottomans had several influential languages: Turkish, spoken by the majority of the people in Anatolia and by the majority of Muslims of the Balkans except some regions such as Albania, Bosnia[97] and the Megleno-Romanian-inhabited Nânti;[98] Persian, only spoken by the educated;[97] Arabic, spoken mainly in Egypt, the Levant, Arabia, Iraq, North Africa, Kuwait and parts of the Horn of Africa and Berber in North Africa. In the last two centuries, usage of these became limited, though, and specific: Persian served mainly as a literary language for the educated,[97] while Arabic was used for Islamic prayers. In the post-Tanzimat period French became the common Western language among the educated.[17]

Because of a low literacy rate among the public (about 2–3% until the early 19th century and just about 15% at the end of the 19th century), ordinary people had to hire scribes as "special request-writers" (arzuhâlcis) to be able to communicate with the government.[99] Some ethnic groups continued to speak within their families and neighborhoods (mahalles) with their own languages, though many non-Muslim minorities such as Greeks and Armenians only spoke Turkish.[100] In villages where two or more populations lived together, the inhabitants often spoke each other's language. In cosmopolitan cities, people often spoke their family languages; many of those who were not ethnic Turks spoke Turkish as a second language.[citation needed]

Religion

Sunni Islam was the prevailing Dīn (customs, legal traditions, and religion) of the Ottoman Empire; the official Madh'hab (school of Islamic jurisprudence) was Hanafi.[101] From the early 16th century until the early 20th century, the Ottoman sultan also served as the caliph, or politico-religious leader, of the Muslim world. Most of the Ottoman Sultans adhered to Sufism and followed Sufi orders, and believed Sufism was the correct way to reach God.[102]

Non-Muslims, particularly Christians and Jews, were present throughout the empire's history. The Ottoman imperial system was charactised by an intricate combination of official Muslim hegemony over non-Muslims and a wide degree of religious tolerance. While religious minorities were never equal under the law, they were granted recognition, protection, and limited freedoms under both Islamic and Ottoman tradition.[103]

Until the second half of the 15th century, the majority of Ottoman subjects were Christian.[55] Non-Muslims remained a significant and economically influential minority, albeit declining significantly by the 19th century, due largely to migration and secession.[103] The proportion of Muslims amounted to 60% in the 1820s, gradually increasing to 69% in the 1870s and 76% in the 1890s.[103] By 1914, less than a fifth of the empire's population (19%) was non-Muslim, mostly made up of Jews and Christian Greeks, Assyrians, and Armenians.[103]

Islam

Turkic peoples practiced a form of shamanism before adopting Islam. The Muslim conquest of Transoxiana under the Abbasids facilitated the spread of Islam into the Turkic heartland of Central Asia. Many Turkic tribes—including the Oghuz Turks, who were the ancestors of both the Seljuks and the Ottomans—gradually converted to Islam and brought religion to Anatolia through their migrations beginning in the 11th century. From its founding, the Ottoman Empire officially supported the Maturidi school of Islamic theology, which emphasized human reason, rationality, the pursuit of science and philosophy (falsafa).[104][105] The Ottomans were among the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence,[106] which was comparatively more flexible and discretionary in its rulings.[107][108]

The Ottoman Empire had a wide variety of Islamic sects, including Druze, Ismailis, Alevis, and Alawites.[109] Sufism, a diverse body of Islamic mysticism, found fertile ground in Ottoman lands; many Sufi religious orders (tariqa), such as the Bektashi and Mevlevi, were either established, or saw significant growth, throughout the empire's history.[110] However, some heterodox Muslim groups were viewed as heretical and even ranked below Jews and Christians in terms of legal protection; Druze were frequent targets of persecution,[111] with Ottoman authorities often citing the controversial rulings of Ibn Taymiyya, a member of the conservative Hanbali school.[112] In 1514, Sultan Selim I ordered the massacre of 40,000 Anatolian Alevis (Qizilbash), whom he considered a fifth column for the rival Safavid Empire.[citation needed]

During Selim's reign, the Ottoman Empire saw an unprecedented and rapid expansion into the Middle East, particularly the conquest of the entire Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt on the early 16th century. These conquests further solidified the Ottoman claim of being an Islamic caliphate, although Ottoman sultans had been claiming the title of caliph since the reign of Murad I (1362–1389).[18] The caliphate was officially transferred from the Mamluks to the Ottoman sultanate in 1517, whose members were recognized as caliphs until the office's abolition on 3 March 1924 by the Republic of Turkey (and the exile of the last caliph, Abdülmecid II, to France).[citation needed]

Christianity and Judaism

In accordance with the Muslim dhimmi system, the Ottoman Empire guaranteed limited freedoms to Christians, Jews, and other "people of the book", such as the right to worship, own property, and be exempt from the obligatory alms (zakat) required of Muslims. However, non-Muslims (or dhimmi) were subject to various legal restrictions, including being forbidden to carry weapons, ride on horseback, or have their homes overlook those of Muslims; likewise, they were required to pay higher taxes than Muslim subjects, including the jizya, which was a key source of state revenue.[113][114] Many Christians and Jews converted to Islam to secure full social and legal status, though most continued to practice their faith without restriction.[citation needed]

The Ottomans developed a unique sociopolitical system known as the millet, which granted non-Muslim communities a large degree of political, legal, and religious autonomy; in essence, members of a millet were subjects of the empire but not subject to the Muslim faith or Islamic law. A millet could govern its own affairs, such as raising taxes and resolving internal legal disputes, with little or no interference from Ottoman authorities, so long as its members were loyal to the sultan and adhered to the rules concerning dhimmi. A quintessential example is the ancient Orthodox community of Mount Athos, which was permitted to retain its autonomy and was never subject to occupation or forced conversion; even special laws were enacted to protect it from outsiders.[115]

The Rum Millet, which encompassed most Eastern Orthodox Christians, was governed by the Byzantine-era Corpus Juris Civilis (Code of Justinian), with the Ecumenical Patriarch designated the highest religious and political authority (millet-bashi, or ethnarch). Likewise, Ottoman Jews came under the authority of the Haham Başı, or Ottoman Chief Rabbi, while Armenians were under the authority of the chief bishop of the Armenian Apostolic Church.[116] As the largest group of non-Muslim subjects, the Rum Millet enjoyed several special privileges in politics and commerce; however, Jews and Armenians were also well represented among the wealthy merchant class, as well as in public administration.[117][118]

Some modern scholars consider the millet system to be an early example of religious pluralism, as it accorded minority religious groups official recognition and tolerance.[119]

Social-political-religious structure

_(cropped).jpg/220px-Subject_Nationalities_of_the_German_Alliance_(1917)_(cropped).jpg)

Beginning in the early 19th century, society, government, and religion were interrelated in a complex, overlapping way that was deemed inefficient by Atatürk, who systematically dismantled it after 1922.[120][121] In Constantinople, the Sultan ruled two distinct domains: the secular government and the religious hierarchy. Religious officials formed the Ulama, who had control of religious teachings and theology, and also the Empire's judicial system, giving them a major voice in day-to-day affairs in communities across the Empire (but not including the non-Muslim millets). They were powerful enough to reject the military reforms proposed by Sultan Selim III. His successor Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) first won ulama approval before proposing similar reforms.[122] The secularisation program brought by Atatürk ended the ulema and their institutions. The caliphate was abolished, madrasas were closed down, and the sharia courts were abolished. He replaced the Arabic alphabet with Latin letters, ended the religious school system, and gave women some political rights. Many rural traditionalists never accepted this secularisation, and by the 1990s they were reasserting a demand for a larger role for Islam.[123]

The Janissaries were a highly formidable military unit in the early years, but as Western Europe modernized its military organization technology, the Janissaries became a reactionary force that resisted all change. Steadily the Ottoman military power became outdated, but when the Janissaries felt their privileges were being threatened, or outsiders wanted to modernize them, or they might be superseded by the cavalrymen, they rose in rebellion. The rebellions were highly violent on both sides, but by the time the Janissaries were suppressed, it was far too late for Ottoman military power to catch up with the West.[124][125] The political system was transformed by the destruction of the Janissaries, a powerful military/governmental/police force, which revolted in the Auspicious Incident of 1826. Sultan Mahmud II crushed the revolt executed the leaders and disbanded the large organization. That set the stage for a slow process of modernization of government functions, as the government sought, with mixed success, to adopt the main elements of Western bureaucracy and military technology.[citation needed]

The Janissaries had been recruited from Christians and other minorities; their abolition enabled the emergence of a Turkish elite to control the Ottoman Empire. A large number of ethnic and religious minorities were tolerated in their own separate segregated domains called millets.[126] They were primarily Greek, Armenian, or Jewish. In each locality, they governed themselves, spoke their own language, ran their own schools, cultural and religious institutions, and paid somewhat higher taxes. They had no power outside the millet. The Imperial government protected them and prevented major violent clashes between ethnic groups.[citation needed]

Ethnic nationalism, based on distinctive religion and language, provided a centripetal force that eventually destroyed the Ottoman Empire.[127] In addition, Muslim ethnic groups, which were not part of the millet system, especially the Arabs and the Kurds, were outside the Turkish culture and developed their own separate nationalism. The British sponsored Arab nationalism in the First World War, promising an independent Arab state in return for Arab support. Most Arabs supported the Sultan, but those near Mecca believed in and supported the British promise.[128]

At the local level, power was held beyond the control of the Sultan by the ayans or local notables. The ayan collected taxes, formed local armies to compete with other notables, took a reactionary attitude toward political or economic change, and often defied policies handed down by the Sultan.[129]

After the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was shrinking, as Russia put on heavy pressure and expanded to its south; Egypt became effectively independent in 1805, and the British later took it over, along with Cyprus. Greece became independent, and Serbia and other Balkan areas became highly restive as the force of nationalism pushed against imperialism. The French took over Algeria and Tunisia. The Europeans all thought that the empire was a sick man in rapid decline. Only the Germans seemed helpful, and their support led to the Ottoman Empire joining the central powers in 1915, with the result that they came out as one of the heaviest losers of the First World War in 1918.[130]

Culture

| Culture of the Ottoman Empire |

|---|

.svg/120px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_Ottoman_Empire_(1882–1922).svg.png) |

| Visual arts |

| Performing arts |

| Languages and literature |

| Sports |

| Other |

The Ottomans absorbed some of the traditions, art, and institutions of cultures in the regions they conquered and added new dimensions to them. Numerous traditions and cultural traits of previous empires (in fields such as architecture, cuisine, music, leisure, and government) were adopted by the Ottoman Turks, who developed them into new forms, resulting in a new and distinctively Ottoman cultural identity. Although the predominant literary language of the Ottoman Empire was Turkish, Persian was the preferred vehicle for the projection of an imperial image.[131]

Slavery was part of Ottoman society,[132] with most slaves employed as domestic servants. Agricultural slavery, like that in the Americas, was relatively rare. Unlike systems of chattel slavery, slaves under Islamic law were not regarded as movable property, and the children of female slaves were born legally free. Female slaves were still sold in the Empire as late as 1908.[133] During the 19th century the Empire came under pressure from Western European countries to outlaw the practice. Policies developed by various sultans throughout the 19th century attempted to curtail the Ottoman slave trade but slavery had centuries of religious backing and sanction and so was never abolished in the Empire.[116]

Plague remained a major scourge in Ottoman society until the second quarter of the 19th century. "Between 1701 and 1750, 37 larger and smaller plague epidemics were recorded in Istanbul, and 31 between 1751 and 1801."[134]

Ottomans adopted Persian bureaucratic traditions and culture. The sultans also made an important contribution in the development of Persian literature.[135]

Language was not an obvious sign of group connection and identity in the 16th century among the rulers of the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran and Abu'l-Khayrid Shibanids of Central Asia.[136] Hence the ruling classes of all three polities were bilingual in varieties of Persian and Turkic.[136] But in the century's final quarter, linguistic adjustments occurred in the Ottoman and Safavid realms defined by a new rigidity that favoured Ottoman Turkish and Persian, respectively.[136]

Education

.jpg/220px-Beyazıt_State_Library_(14667026514).jpg)

In the Ottoman Empire, each millet established a schooling system serving its members.[137] Education was therefore largely divided on ethnic and religious lines: few non-Muslims attended schools for Muslim students, and vice versa. Most institutions that served all ethnic and religious groups taught in French or other languages.[138]

Several "foreign schools" (Frerler mektebleri) operated by religious clergy primarily served Christians, although some Muslim students attended.[137] Garnett described the schools for Christians and Jews as "organised upon European models", with "voluntary contributions" supporting their operation and most of them "well attended" and with "a high standard of education".[139]

Literature

The two primary streams of Ottoman written literature are poetry and prose. Poetry was by far the dominant stream. The earliest work of Ottoman historiography for example, the İskendernâme, was composed by the poet Taceddin Ahmedi (1334–1413).[140] Until the 19th century, Ottoman prose did not contain any examples of fiction: there were no counterparts to, for instance, the European romance, short story, or novel. Analog genres did exist, though, in both Turkish folk literature and in Divan poetry.[citation needed]

Ottoman Divan poetry was a highly ritualized and symbolic art form. From the Persian poetry that largely inspired it, it inherited a wealth of symbols whose meanings and interrelationships—both of similitude (مراعات نظير mura'ât-i nazîr / تناسب tenâsüb) and opposition (تضاد tezâd) were more or less prescribed. Divan poetry was composed through the constant juxtaposition of many such images within a strict metrical framework, allowing numerous potential meanings to emerge. The vast majority of Divan poetry was lyric in nature: either gazels (which make up the greatest part of the repertoire of the tradition), or kasîdes. But there were other common genres, especially the mesnevî, a kind of verse romance and thus a variety of narrative poetry; the two most notable examples of this form are the Leyli and Majnun of Fuzuli and the Hüsn ü Aşk of Şeyh Gâlib. The Seyahatnâme of Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) is an outstanding example of travel literature.[citation needed]

.JPG/170px-Nedim_(divan_edb.şairi).JPG)

Until the 19th century, Ottoman prose did not develop to the extent that contemporary Divan poetry did. A large part of the reason was that much prose was expected to adhere to the rules of sec (سجع, also transliterated as seci), or rhymed prose,[141] a type of writing descended from the Arabic saj' that prescribed that between each adjective and noun in a string of words, such as a sentence, there must be a rhyme. Nevertheless, there was a tradition of prose in the literature of the time, though it was exclusively nonfictional. One apparent exception was Muhayyelât (Fancies) by Giritli Ali Aziz Efendi, a collection of stories of the fantastic written in 1796, though not published until 1867. The first novel published in the Ottoman Empire was Vartan Pasha's 1851 The Story of Akabi (Turkish: Akabi Hikyayesi). It was written in Turkish but with Armenian script.[142][143][144][145]

Due to historically close ties with France, French literature constituted the major Western influence on Ottoman literature in the latter half of the 19th century. As a result, many of the same movements prevalent in France during this period had Ottoman equivalents; in the developing Ottoman prose tradition, for instance, the influence of Romanticism can be seen during the Tanzimat period, and that of the Realist and Naturalist movements in subsequent periods; in the poetic tradition, on the other hand, the influence of the Symbolist and Parnassian movements was paramount.[citation needed]

Many of the writers in the Tanzimat period wrote in several different genres simultaneously; for instance, the poet Namık Kemal also wrote the important 1876 novel İntibâh (Awakening), while the journalist İbrahim Şinasi is noted for writing, in 1860, the first modern Turkish play, the one-act comedy Şair Evlenmesi (The Poet's Marriage). An earlier play, a farce titled Vakâyi'-i 'Acibe ve Havâdis-i Garibe-yi Kefşger Ahmed (The Strange Events and Bizarre Occurrences of the Cobbler Ahmed), dates from the beginning of the 19th century, but there is doubt about its authenticity. In a similar vein, the novelist Ahmed Midhat Efendi wrote important novels in each of the major movements: Romanticism (Hasan Mellâh yâhud Sırr İçinde Esrâr, 1873; Hasan the Sailor, or The Mystery Within the Mystery), Realism (Henüz on Yedi Yaşında, 1881; Just Seventeen Years Old), and Naturalism (Müşâhedât, 1891; Observations). This diversity was, in part, due to Tanzimat writers' wish to disseminate as much of the new literature as possible, in the hopes that it would contribute to a revitalization of Ottoman social structures.[146]

Media

The media of the Ottoman Empire was diverse, with newspapers and journals published in languages including French,[147] Greek,[148] and German.[116] Many of these publications were centred in Constantinople,[149] but there were also French-language newspapers produced in Beirut, Salonika, and Smyrna.[150] Non-Muslim ethnic minorities in the empire used French as a lingua franca and used French-language publications,[147] while some provincial newspapers were published in Arabic.[151] The use of French in the media persisted until the end of the empire in 1923 and for a few years thereafter in the Republic of Turkey.[147]

Architecture

.jpg/220px-Exterior_of_Sultan_Ahmed_I_Mosque%2C_(old_name_P1020390.jpg).jpg)

The architecture of the empire developed from earlier Seljuk Turkish architecture, with influences from Byzantine and Iranian architecture and other architectural traditions in the Middle East.[152][153][154] Early Ottoman architecture experimented with multiple building types over the course of the 13th to 15th centuries, progressively evolving into the Classical Ottoman style of the 16th and 17th centuries, which was also strongly influenced by the Hagia Sophia.[154][155] The most important architect of the Classical period is Mimar Sinan, whose major works include the Şehzade Mosque, Süleymaniye Mosque, and Selimiye Mosque.[156][157] The greatest of the court artists enriched the Ottoman Empire with many pluralistic artistic influences, such as mixing traditional Byzantine art with elements of Chinese art.[158] The second half of the 16th century also saw the apogee of certain decorative arts, most notably in the use of Iznik tiles.[159]

Beginning in the 18th century, Ottoman architecture was influenced by the Baroque architecture in Western Europe, resulting in the Ottoman Baroque style.[160] Nuruosmaniye Mosque is one of the most important examples from this period.[161][162] The last Ottoman period saw more influences from Western Europe, brought in by architects such as those from the Balyan family.[163] Empire style and Neoclassical motifs were introduced and a trend towards eclecticism was evident in many types of buildings, such as the Dolmabaçe Palace.[164] The last decades of the Ottoman Empire also saw the development of a new architectural style called neo-Ottoman or Ottoman revivalism, also known as the First National Architectural Movement,[165] by architects such as Mimar Kemaleddin and Vedat Tek.[163]

Ottoman dynastic patronage was concentrated in the historic capitals of Bursa, Edirne, and Istanbul (Constantinople), as well as in several other important administrative centres such as Amasya and Manisa. It was in these centres that most important developments in Ottoman architecture occurred and that the most monumental Ottoman architecture can be found.[166] Major religious monuments were typically architectural complexes, known as a külliye, that had multiple components providing different services or amenities. In addition to a mosque, these could include a madrasa, a hammam, an imaret, a sebil, a market, a caravanserai, a primary school, or others.[167] These complexes were governed and managed with the help of a vakıf agreement (Arabic waqf).[167] Ottoman constructions were still abundant in Anatolia and in the Balkans (Rumelia), but in the more distant Middle Eastern and North African provinces older Islamic architectural styles continued to hold strong influence and were sometimes blended with Ottoman styles.[168][169]

Decorative arts

The tradition of Ottoman miniatures, painted to illustrate manuscripts or used in dedicated albums, was heavily influenced by the Persian art form, though it also included elements of the Byzantine tradition of illumination and painting.[170] A Greek academy of painters, the Nakkashane-i-Rum, was established in the Topkapi Palace in the 15th century, while early in the following century a similar Persian academy, the Nakkashane-i-Irani, was added. Surname-i Hümayun (Imperial Festival Books) were albums that commemorated celebrations in the Ottoman Empire in pictorial and textual detail.[citation needed]

Ottoman illumination covers non-figurative painted or drawn decorative art in books or on sheets in muraqqa or albums, as opposed to the figurative images of the Ottoman miniature. It was a part of the Ottoman Book Arts together with the Ottoman miniature (taswir), calligraphy (hat), Islamic calligraphy, bookbinding (cilt) and paper marbling (ebru). In the Ottoman Empire, illuminated and illustrated manuscripts were commissioned by the Sultan or the administrators of the court. In Topkapi Palace, these manuscripts were created by the artists working in Nakkashane, the atelier of the miniature and illumination artists. Both religious and non-religious books could be illuminated. Also, sheets for albums levha consisted of illuminated calligraphy (hat) of tughra, religious texts, verses from poems or proverbs, and purely decorative drawings.[citation needed]

The art of carpet weaving was particularly significant in the Ottoman Empire, carpets having an immense importance both as decorative furnishings, rich in religious and other symbolism and as a practical consideration, as it was customary to remove one's shoes in living quarters.[171] The weaving of such carpets originated in the nomadic cultures of central Asia (carpets being an easily transportable form of furnishing), and eventually spread to the settled societies of Anatolia. Turks used carpets, rugs, and kilims not just on the floors of a room but also as a hanging on walls and doorways, where they provided additional insulation. They were also commonly donated to mosques, which often amassed large collections of them.[172]

Music and performing arts

Ottoman classical music was an important part of the education of the Ottoman elite. A number of the Ottoman sultans have accomplished musicians and composers themselves, such as Selim III, whose compositions are often still performed today. Ottoman classical music arose largely from a confluence of Byzantine, Armenian, Arabic, and Persian music. Compositionally, it is organized around rhythmic units called usul, which are somewhat similar to meter in Western music, and melodic units called makam, which bear some resemblance to Western musical modes.[citation needed]

The instruments used are a mixture of Anatolian and Central Asian instruments (the saz, the bağlama, the kemence), other Middle Eastern instruments (the ud, the tanbur, the kanun, the ney), and—later in the tradition—Western instruments (the violin and the piano). Because of a geographic and cultural divide between the capital and other areas, two broadly distinct styles of music arose in the Ottoman Empire: Ottoman classical music and folk music. In the provinces, several different kinds of folk music were created. The most dominant regions with their distinguished musical styles are Balkan-Thracian Türküs, North-Eastern (Laz) Türküs, Aegean Türküs, Central Anatolian Türküs, Eastern Anatolian Türküs, and Caucasian Türküs. Some of the distinctive styles were: Janissary music, Roma music, belly dance, and Turkish folk music.[citation needed]

The traditional shadow play called Karagöz and Hacivat was widespread throughout the Ottoman Empire and featured characters representing all of the major ethnic and social groups in that culture.[173][174] It was performed by a single puppet master, who voiced all of the characters, and accompanied by tambourine (def). Its origins are obscure, deriving perhaps from an older Egyptian tradition, or possibly from an Asian source.[citation needed]

-

The shadow play Karagöz and Hacivat was widespread throughout the Ottoman Empire.

-

A musical gathering in the 18th century

-

Acrobacy in Surname-i Hümayun

Cuisine

Ottoman cuisine is the cuisine of the capital, Constantinople (Istanbul), and the regional capital cities, where the melting pot of cultures created a common cuisine that most of the population regardless of ethnicity shared. This diverse cuisine was honed in the Imperial Palace's kitchens by chefs brought from certain parts of the Empire to create and experiment with different ingredients. The creations of the Ottoman Palace's kitchens filtered to the population, for instance through Ramadan events, and through the cooking at the Yalıs of the Pashas, and from there on spread to the rest of the population.[citation needed]

Much of the cuisine of former Ottoman territories today is descended from a shared Ottoman cuisine, especially Turkish, and including Greek, Balkan, Armenian, and Middle Eastern cuisines.[175] Many common dishes in the region, descendants of the once-common Ottoman cuisine, include yogurt, döner kebab/gyro/shawarma, cacık/tzatziki, ayran, pita bread, feta cheese, baklava, lahmacun, moussaka, yuvarlak, köfte/keftés/kofta, börek/boureki, rakı/rakia/tsipouro/tsikoudia, meze, dolma, sarma, rice pilaf, Turkish coffee, sujuk, kashk, keşkek, manti, lavash, kanafeh, and more.[citation needed]

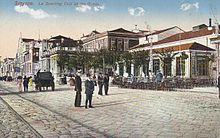

Sports

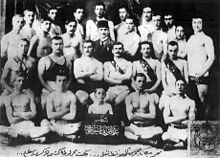

The main sports Ottomans were engaged in were Turkish wrestling, hunting, Turkish archery, horseback riding, equestrian javelin throw, arm wrestling, and swimming. European model sports clubs were formed with the spreading popularity of football matches in 19th century Constantinople. The leading clubs, according to timeline, were Beşiktaş Gymnastics Club (1903), Galatasaray Sports Club (1905), Fenerbahçe Sports Club (1907), MKE Ankaragücü (formerly Turan Sanatkarangücü) (1910) in Constantinople. Football clubs were formed in other provinces too, such as Karşıyaka Sports Club (1912), Altay Sports Club (1914) and Turkish Fatherland Football Club (later Ülküspor) (1914) of İzmir.

Science and technology

Over the course of Ottoman history, the Ottomans managed to build a large collection of libraries complete with translations of books from other cultures, as well as original manuscripts.[176] A great part of this desire for local and foreign manuscripts arose in the 15th century. Sultan Mehmet II ordered Georgios Amiroutzes, a Greek scholar from Trabzon, to translate and make available to Ottoman educational institutions the geography book of Ptolemy. Another example is Ali Qushji—an astronomer, mathematician and physicist originally from Samarkand—who became a professor in two madrasas and influenced Ottoman circles as a result of his writings and the activities of his students, even though he only spent two or three years in Constantinople before his death.[177]

Taqi al-Din built the Constantinople observatory of Taqi ad-Din in 1577, where he carried out observations until 1580. He calculated the eccentricity of the Sun's orbit and the annual motion of the apogee.[178] However, the observatory's primary purpose was almost certainly astrological rather than astronomical, leading to its destruction in 1580 due to the rise of a clerical faction that opposed its use for that purpose.[179] He also experimented with steam power in Ottoman Egypt in 1551, when he described a steam jack driven by a rudimentary steam turbine.[180]

In 1660, the Ottoman scholar Ibrahim Efendi al-Zigetvari Tezkireci translated Noël Duret's French astronomical work (written in 1637) into Arabic.[182]

Şerafeddin Sabuncuoğlu was the author of the first surgical atlas and the last major medical encyclopaedia from the Islamic world. Though his work was largely based on Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi's Al-Tasrif, Sabuncuoğlu introduced many innovations of his own. Female surgeons were also illustrated for the first time.[183] Since, the Ottoman Empire is credited with the invention of several surgical instruments in use such as forceps, catheters, scalpels and lancets as well as pincers.[184][better source needed]

An example of a watch that measured time in minutes was created by an Ottoman watchmaker, Meshur Sheyh Dede, in 1702.[185]

In the early 19th century, Egypt under Muhammad Ali began using steam engines for industrial manufacturing, with industries such as ironworks, textile manufacturing, paper mills and hulling mills moving towards steam power.[186] Economic historian Jean Batou argues that the necessary economic conditions existed in Egypt for the adoption of oil as a potential energy source for its steam engines later in the 19th century.[186]

In the 19th century, Ishak Efendi is credited with introducing the then current Western scientific ideas and developments to the Ottoman and wider Muslim world, as well as the invention of a suitable Turkish and Arabic scientific terminology, through his translations of Western works.[citation needed]

See also

- 16 Great Turkic Empires

- Bibliography of the Ottoman Empire

- Empire of the Sultans

- Gunpowder empires

- Historiography of the Ottoman Empire

- Outline of the Ottoman Empire

- List of battles involving the Ottoman Empire

- List of foreigners who were in the service of the Ottoman Empire

- List of Ottoman conquests, sieges and landings

- List of wars involving the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman wars in Europe

- Turkic history

References

Footnotes

- ^ In Ottoman Turkish, the city was known by various names, among which were Ḳosṭanṭīnīye (قسطنطينيه) (replacing the suffix -polis with the Arabic suffix), Istanbul (استنبول) and Islambol (اسلامبول, lit. 'full of Islam'); see Names of Istanbul). Kostantiniyye became obsolete in Turkish after the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923,[5] and after Turkey's transition to Latin script in 1928,[6] the Turkish government in 1930 requested that foreign embassies and companies use Istanbul, and that name became widely accepted internationally.[7] Eldem Edhem, author of an entry on Istanbul in Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, stated that the majority of the Turkish people c. 2010, including historians, believe using "Constantinople" to refer to the Ottoman-era city is "politically incorrect" despite any historical accuracy.[5]

- ^ Liturgical language; among Arabic-speaking citizens

- ^ Court, diplomacy, poetry, historiographical works, literary works, taught in state schools, and offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

- ^ Among Greek-speaking community; spoken by some sultans.

- ^ Decrees in the 15th century.[16]

- ^ Foreign language among educated people in the post-Tanzimat/late imperial period.[17]

- ^ The sultan from 1512 to 1520.

- ^ 1 November 1922 marks the formal ending of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed VI departed Constantinople on 17 November 1922.

- ^ The Treaty of Sèvres (10 August 1920) afforded a small existence to the Ottoman Empire. On 1 November 1922, the Grand National Assembly (GNAT) abolished the sultanate and declared that all the deeds of the Ottoman regime in Constantinople were null and void as of 16 March 1920, the date of the occupation of Constantinople under the terms of the Treaty of Sèvres. The international recognition of the GNAT and the Government of Ankara was achieved through the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923. The Grand National Assembly of Turkey promulgated the Republic on 29 October 1923, which ended the Ottoman Empire in history.

- ^ /ˈɒtəmən/

• Ottoman Turkish: دولت عليه عثمانيه, romanized: Devlet-i ʿAlīye-i ʿOsmānīye, lit. 'Sublime Ottoman State'

• Turkish: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu or Osmanlı Devleti

• French: Empire ottoman, the common Western language among the educated in the late Ottoman Empire[17]

Minority languages:

• Western Armenian: Օսմանեան տէրութիւն, romanized: Osmanean Têrut'iwn, lit. 'Ottoman Authority/Governance/Rule', Օսմանեան պետութիւն, Osmanean Petut'iwn, 'Ottoman State' and Օսմանեան կայսրութիւն, Osmanean Kaysrut'iwn, 'Ottoman Empire'

• Bulgarian: Османска империя, romanized: Otomanskata Imperiya; Отоманска империя is an archaic version. The definite article forms Османската империя and Османска империя were synonymous

• Greek: Оθωμανική Επικράτεια, romanized: Othōmanikē Epikrateia and Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria

• Ladino: Imperio otomano[23] - ^ The Ottoman dynasty also held the title "caliph" from the Ottoman victory over the Mamluk Sultanate of Cairo in the Battle of Ridaniya in 1517 to the abolition of the Caliphate by the Turkish Republic in 1924.

- ^ The empire also temporarily gained authority over distant overseas lands through declarations of allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan and Caliph, such as the declaration by the Sultan of Aceh in 1565, or through temporary acquisitions of islands such as Lanzarote in the Atlantic Ocean in 1585.[29]

Citations

- ^ McDonald, Sean; Moore, Simon (20 October 2015). "Communicating Identity in the Ottoman Empire and Some Implications for Contemporary States". Atlantic Journal of Communication. 23 (5): 269–283. doi:10.1080/15456870.2015.1090439. ISSN 1545-6870. S2CID 146299650. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford; Shaw, Ezel (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8.

- ^ Atasoy & Raby 1989, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b "In 1363 the Ottoman capital moved from Bursa to Edirne, although Bursa retained its spiritual and economic importance." Ottoman Capital Bursa Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Official website of Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Turkey. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ a b Edhem, Eldem (2010). "Istanbul". In Gábor, Ágoston; Masters, Bruce Alan (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, all previous names were abandoned and Istanbul came to designate the entire city.

- ^ Shaw, Stanford J.; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977b). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 2: Reform, Revolution, and Republic: The Rise of Modern Turkey 1808–1975. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511614972. ISBN 9780511614972.

- ^ Shaw & Shaw 1977b, p. 386, volume 2; Robinson (1965). The First Turkish Republic. p. 298.; Society (4 March 2014). "Istanbul, not Constantinople". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.)

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian Learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World: The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. pp. 88–89.

As the Ottoman Turks learned Persian, the language and the culture it carried seeped not only into their court and imperial institutions but also into their vernacular language and culture. The appropriation of Persian, both as a second language and as a language to be steeped together with Turkish, was encouraged notably by the sultans, the ruling class, and leading members of the mystical communities.

- ^ Tezcan, Baki (2012). "Ottoman Historical Writing". In Rabasa, José (ed.). The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800 The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 3: 1400–1800. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–211.

Persian served as a 'minority' prestige language of culture at the largely Turcophone Ottoman court.

- ^ Flynn, Thomas O. (2017). The Western Christian Presence in the Russias and Qājār Persia, c. 1760–c. 1870. Brill. p. 30. ISBN 978-90-04-31354-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

- ^ Fortna, B. (2012). Learning to Read in the Late Ottoman Empire and the Early Turkish Republic. Springer. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-230-30041-5. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Although in the late Ottoman period Persian was taught in the state schools...

- ^ Spuler, Bertold (2003). Persian Historiography and Geography. Pustaka Nasional Pte. p. 68. ISBN 978-9971-77-488-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

On the whole, the circumstance in Turkey took a similar course: in Anatolia, the Persian language had played a significant role as the carrier of civilization. [...] where it was at time, to some extent, the language of diplomacy [...] However Persian maintained its position also during the early Ottoman period in the composition of histories and even Sultan Salim I, a bitter enemy of Iran and the Shi'ites, wrote poetry in Persian. Besides some poetical adaptations, the most important historiographical works are: Idris Bidlisi's flowery "Hasht Bihist", or Seven Paradises, begun in 1502 by the request of Sultan Bayazid II and covering the first eight Ottoman rulers...

- ^ Fetvacı, Emine (2013). Picturing History at the Ottoman Court. Indiana University Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-253-00678-3. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Persian literature, and belles-lettres in particular, were part of the curriculum: a Persian dictionary, a manual on prose composition; and Sa'dis 'Gulistan', one of the classics of Persian poetry, were borrowed. All these titles would be appropriate in the religious and cultural education of the newly converted young men.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan; Melville, Charles, eds. (359). Persian Historiography: A History of Persian Literature. Vol. 10. Bloomsbury. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-85773-657-4. Archived from the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

Persian held a privileged place in Ottoman letters. Persian historical literature was first patronized during the reign of Mehmed II and continued unabated until the end of the 16th century.

- ^ Inan, Murat Umut (2019). "Imperial Ambitions, Mystical Aspirations: Persian learning in the Ottoman World". In Green, Nile (ed.). The Persianate World The Frontiers of a Eurasian Lingua Franca. University of California Press. p. 92 (note 27).

Though Persian, unlike Arabic, was not included in the typical curriculum of an Ottoman madrasa, the language was offered as an elective course or recommended for study in some madrasas. For those Ottoman madrasa curricula featuring Persian, see Cevat İzgi, Osmanlı Medreselerinde İlim, 2 vols. (Istanbul: İz, 1997),1: 167–169.

- ^ Ayşe Gül Sertkaya (2002). "Şeyhzade Abdurrezak Bahşı". In György Hazai (ed.). Archivum Ottomanicum. Vol. 20. pp. 114–115. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 23 October 2022.

As a result, we can claim that Şeyhzade Abdürrezak Bahşı was a scribe lived in the palaces of Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his son Bayezid-i Veli in the 15th century, wrote letters (bitig) and firmans (yarlığ) sent to Eastern Turks by Mehmed II and Bayezid II in both Uighur and Arabic scripts and in East Turkestan (Chagatai) language.

- ^ a b c Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Würzburg: Orient-Institut Istanbul. pp. 21–51. Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019. (info page on book Archived 20 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine at Martin Luther University) // Cited: p. 26 (pdf p. 28): "French had become a sort of semi-official language in the Ottoman Empire in the wake of the Tanzimat reforms.[...] It is true that French was not an ethnic language of the Ottoman Empire. But it was the only Western language which would become increasingly widespread among educated persons in all linguistic communities."

- ^ a b c Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard (1995). The Cambridge History of Islam: The Indian sub-continent, South-East Asia, Africa and the Muslim west. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-521-22310-2. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Pamuk, Şevket (2000). A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-521-44197-8. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2022.

The Ottomans began to strike coins in the name of Orhan Bey in 1326. These earliest coins carried inscriptions such as "the great Sultan, Orhan son of Osman" [...] Ottoman historiography has adopted 1299 as the date for the foundation of the state. 1299 might represent the date at which the Ottomans finally obtained their independence from the Seljuk sultan at Konya. Probably, they were forced at the same time, or very soon thereafter, to accept the overlordship of the Ilkhanids [...] Numismatic evidence thus suggest that independence did not really occur until 1326.

- ^ a b c Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 498. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. ISSN 0020-8833. JSTOR 2600793. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 223. ISSN 1076-156X. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2016.